It has been several months since I finished my three-year-long travel. Although I have lived in different places and worked on various subjects throughout my life, I reached my own Nirvana during the three years. When I recollect who I was at the beginning of my journey, I realize I have changed so much that I can barely understand why I used to be so pessimistic and ignorant.

What does travel do? Everyone has their answers. I became a better person with a refined understanding of people, history, culture, and above all, myself.

Now I am back to everyday life with a job and a permanent address!

My first impression of Cincinnati is the view of skyscrapers on I-71/75N in Kentucky.

A new city, a new life

History tells us everything today is caused by some events in the past until the origin of our universe. Although I do not need to trace back to the distant past, my story did begin a while ago in Cincinnati, Ohio, a typical mid-sized American city.

My connection with Cincinnati began in a harsh winter during my interview for the doctoral program. Having lived in southern Texas for more than two years, the moment I walked out of the airport was unforgettable. The pristine snow and the piercing wind brought me into another world. Even today, I still remember the wind blowing up my face and penetrating my suit on the interview day.

Everything went well in my interview, and I especially enjoyed the conversations with professors and students. Soon later, I received an offer to the doctoral program. Then I moved to Cincinnati in the summer. Surprisingly, I could not tell the weather difference between Texas and Ohio this time, probably due to the method of travel: I moved by car, similar to the effect of acclimation when we go to high altitude. I should have taken precious free time to explore my new home, but I was apathetic about new stuff back then. What made it even worse was that I underrated the hardship and setbacks of the upcoming doctoral program. It cost me a tremendous amount of time and energy to stay on track for the subsequent five-year study.

In the beginning, I was excited to be in touch with all the interesting topics at the frontier of biomedical science. Also, I appreciated my program offering numerous opportunities to study animal development in different contexts, including how organs are formed in multiple animal models. In my first year, I rotated three labs with dramatically different focuses:

- The transcriptional regulation in Drosophila

- The lung development in frogs

- The heart development in zebrafish

Eventually, I joined the last one. It turned out the trek to the end was not flat at all!

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center is one of the top biomedical research institutions to study developmental biology.

Epic fail!

Science is about the underlying mechanism of how the natural world works. Respectively, the truth is always hidden behind the scene. The job of scientists is to find out the cause of the phenomena on the surface. Because nobody can foresee what is not shown, the method is to propose a hypothesis and test it through experiments.

Two challenges stand in front of every researcher. The first is how to approach the right question. Indeed, I could not tell what the question meant many years ago. As it is said, the more you know, the more unknown you know. Scientists who dedicate many years to gaining knowledge in a field fully comprehend how little is known and how much more effort is needed to depict the complete picture. When we accomplished the Human Genome Project, many thought we could finally understand how genetics work in our bodies. Over twenty years passed, and we are still working towards the goal. Gene is less important than we thought. Many other species, such as mice and zebrafish, have more or less the same amount of genes, and most are functionally similar to ours. Nowadays, we realize that the phenotypic difference relies on regulating these genes (e.g., where and when a gene is expressed).

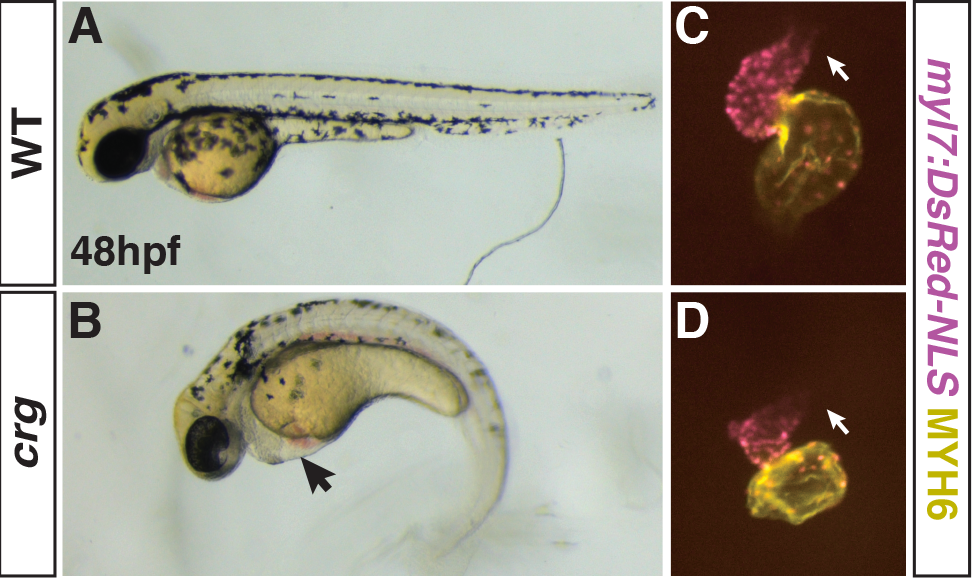

Therefore, we could ask as many questions about any scientific topic as possible. In my project, we discovered a mutant with early cardiac defects (a smaller distorted heart). As I learned that cardiac development requires the coordination of multiple cell types and the interaction between cardiac cells and the surroundings, I proposed to examine all known factors involved in early cardiac development. To assess these factors, I even made a multiple-year-long plan. Against the advice from my mentor, I insisted on my “well-thought” strategy. Unsurprisingly, I was eventually overwhelmed by my ambitions, as experiments did not follow the plan. After struggling for two years, I finally took advice from my mentor: ask one question at a time. For example, what causes a smaller heart? Fewer cells or smaller cells? If there are fewer cells, why? Less proliferation or differentiation? Although I could only tell a small part of the story behind what I observed, I answered a critical question in my field. After all, attempting to finish a project that requires decades of hard work and luck as a doctoral student in less than five years is never a wise decision.

Besides underestimating the amount of work in my project, I also overestimated my learning skills. In the past decade, computational analysis has become an essential tool for almost all branches of science, including biomedical sciences. As most biologists have never been trained as computer scientists, it may be a valuable opportunity to gain the skills and outcompete fellow scientists in my field. Then I proposed to conduct costly experiments to generate data for my analysis. But my mentor disagreed based on two points: first, it takes time to have the expertise, and I could make better use of my time for something more important; second, these experiments do not help to answer questions in my hypothesis. Unfortunately, I was too stubborn to listen to my advisor. Instead, I put my work aside and shifted my focus to taking online courses. Ultimately, it did not lead me anywhere, as the practice is far more critical for coding than taking a class. After wasting several months, I conceded. Recently, I heard that a fellow student from my class is working on a bioinformatics project. Interestingly, he only gained the skill when his project required it. Suddenly, I realized that I used to idealize my plan so much that I was always caught by surprise in reality.

The other challenge is facing tedious work or repetitive failures in most cases. Research means searching for something again and again. We might find something at the end, but often nothing after exhausting all means. Negative results always lead to frustration. After many failures, I even started doubting why I was still doing research. Indeed, these setbacks are common among scientists, especially junior members. The key is how to deal with it mentally.

If I were asked what to do today, I would be open to resort to help from colleagues or not be hesitant to take some days off. Ridiculously, all I did then was repeat the same experiments. As Albert Einstein said, insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. I turned out to be mad to some degree after such stupidity. At some point, we must accept that the hypothesis is disapproved or technical barriers are too high to overcome. Unfortunately, I was too ignorant and proud to admit I was wrong and refused to think alternatively.

The tiny zebrafish embryos accompanied me in my five-year study. Here is the picture of the mutant embryos and developing hearts.

Talk too much, listen too little?

In elementary school, my teacher asked us what we wanted to be in the future. I answered I wanted to be a scientist. Then she asked me why? I said I do not need to worry about other people as scientists are not concerned about complicated social interactions. I was right that interpersonal relationships are complex. At the same time, I was wrong as modern scientists work in groups to move forward rather than individuals, such as Nicolas Copernicus and Charles Darwin fought against the orthodox. Sadly, I only changed my obsolete perception at the end of my doctoral program.

After so many years, I still remember that my doctoral mentor told me not to try to make friends with everyone. It looks pretty amusing that I could not understand the simple idea. As a molecular biologist, I learned how much effort it takes to revert a differentiated cell to a pluripotential status. The same applies to the human being. Everyone grows up in their respective environment and forms different personalities and interests. It would be almost impossible to remove our marks from the past and turn them into a new nature so that they can be more compatible with others.

My first unpleasant encounter occurred with a labmate Ariel. She is a calm girl from Minnesota. When I brought the sunshine from Texas, she immediately felt uncomfortable. Laughably, I even tried to make friends with her considering our conflicting personalities. Once I made a joke saying that her personality is as cold as ice in Minnesota. It only made our relationship more strained. Such incidents happened again and again with other people until nobody wanted to interact with me. Ironically, I did not feel upset. Instead, I considered others irritating and disrespectful.

After a while, my mentor pointed out my lack of communication skills and encouraged me to improve my English. My arrogance again prevented me from self-reflection, and I declined to take his advice. I was only aware of how horrible my English was until I asked a labmate to review the manuscript of my doctoral thesis! It reminded me of a friend advising me to be less talkative several years earlier. At that moment, I realized I was so egocentric that I have exasperated many people since college. How shameful I had been on the wrong track for a long time!

The view from my apartment complex in the winter of Cincinnati.

Change? Yes, I can.

Changes in biology, such as genetic mutations, are detrimental until nature works against the status quo. Human behaviors are no exception. In 2008, Barack Obama received acclaim from audiences all over the country after his famous speech ‘Yes, we can.’ in the US presidential election campaign because people in America were looking forward to a change after the disastrous financial crisis. As an ancient Chinese proverb says, ‘failure is the mother of success.’ It is time to change when the old way does not work anymore.

After experiencing setbacks one after another during my five-year study, I finally recognized I needed to get out of my comfort zone and try a different lifestyle, especially after a long break in 2018. During the six weeks away from the lab, I visited family and friends in China for the first time in seven years, gave a presentation at a conference in Japan, and had my first glimpse of Europe. I was amazed that the world is far more existing than my lab and apartment, with people living diverse lifestyles. In comparison, I am nothing more than the frog in the well from a fable by Zhuang Zi. Suddenly, I felt desperate to stay away from the everyday routine and try new things. Immediately after finishing my degree, I decided to put my career aside and step out of my social bubble, even though I did not know where it would end.

Then I embarked on my adventure.